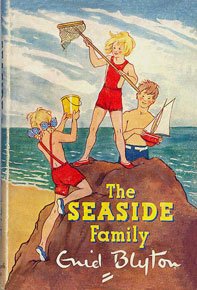

The Seaside Family

Book Details...

First edition: 1950

Publisher: Lutterworth Press

Illustrator: Ruth Gervis

Category: Caravan Family

Genre: Family

Type: Novels/Novelettes

Publisher: Lutterworth Press

Illustrator: Ruth Gervis

Category: Caravan Family

Genre: Family

Type: Novels/Novelettes

On This Page...

Reprints

1. 1982 Sparrow, illustrations and cover by Joyce Smith and David Dowland

2. 1989 Beaver, illustrations by Joyce Smith and David Dowland, cover uncredited

3. 1991 Mammoth, illustrations by Ruth Gervis, cover by Kim Palmer

4. 1997 Mammoth, illustrations by Ruth Gervis, cover by Richard Jones

5. 2017 Egmont, illustrations and cover by Aleksei Bitskoff

2. 1989 Beaver, illustrations by Joyce Smith and David Dowland, cover uncredited

3. 1991 Mammoth, illustrations by Ruth Gervis, cover by Kim Palmer

4. 1997 Mammoth, illustrations by Ruth Gervis, cover by Richard Jones

5. 2017 Egmont, illustrations and cover by Aleksei Bitskoff

Wraparound dustwrapper from the 1st edition, November 1950 @ 4/-, illustrated by Ruth Gervis

Frontis from the 1st edition, illustrated by Ruth Gervis

However, if we take a closer look at some of the traits Ben possesses as a character and compare them with Enid's 'confessions' to Dorothy Richards on page 109 — 110 of Barbara Stoney's Biography, we come to realise that again, like 'The Pole Star Family', Enid has given us a very personal piece of writing in The Seaside Family. Much of Ben's character seemingly mirrors the way Enid viewed herself, especially when it comes to his beliefs about God, as we shall see later.

The similarities between The Seaside Family and Enid's earlier books, such as The Enchanted Wood, in that a visiting character is introduced early on, are interesting to note, as we come to realise almost straight away that in the little boy, Ben Johns, we have a character a lot like Curious Connie, who needs to learn a few lessons about the 'correct' way to behave before he can become a caravan family member! Like Curious Connie, Enid seems only to introduce him so that the central child characters, now much more independent and reliable than in the first book of the series, can teach him how to behave. He is a typically 'weak' little boy, destined to be made stronger by the time the book comes to a close, with 'straight fair hair and rather pale blue eyes' but with a 'nice, sudden smile'. This description is typical of many of Enid's descriptions of 'weak' characters, who often seem pale in both character and complexion compared to the more 'robust' central characters (Gus, for example in The Circus of Adventure), but who, if they are to redeem themselves later on, often possess a twinkle in their eye, or a 'sudden smile'. Also typical is the characters out-spoken-ness when it comes to their thoughts on the 'Caravan Family's' way of life, which Ben dismisses with the words, 'I always thought it was gipsies who did that [live in a caravan] I don't know that I'm going to like it. I'd rather live in a house.' The reaction of Mike, Belinda and Ann is also typical, when they stare at Benjy 'without a word' and Ann is cross. This is very similar to the Faraway Tree children, who are initially so keen to share the delights of the Enchanted Wood with Connie, but who are shocked at finding that some children do not see the merits of the way of life they are used to and are apt to pour scorn on the very things the central characters love. Many children have surely experienced this feeling at some point or another, be it over a house, pet or just a toy, and it is a great example of Enid being able to get right into the mind of the child reader and expressing how they would feel.

The three main children do not take kindly to Benjy's remarks about their home, and at once take a dislike to the little boy, which again, is typical of many a start to many an Enid Blyton story. For example, the children all have their special jobs to do, but Benjy doesn't see why he should contribute his help in any way, even suggesting that the girls make up his bunk every morning for him, saying 'That's not boys work — making beds.' To which he gets the reply he deserves from Ann; 'Our Daddy often makes his own bunk, and if he can do it, so can you.' proving that Enid believed in equal opportunities a long time before her critics were telling her that she didn't!

As mentioned earlier, like the Adventure books, the settings of these 'family' stories are usually the most important feature of the books. The Seaside Family is possibly the one exception. The seaside setting is about the most down to earth of the six books, and yet strangely it also remains the most unreal. Enid's descriptions of life in a caravan, narrow boat and on board an ocean liner are all very realistic, and help add immeasurably to the overall feel of the books, but her descriptions of the seaside setting somehow never seem to ring true. It seems to be a strange amalgamation of all of the seaside settings Enid has used previously, and too perfect to ever be a real place, with its sandy beach, high cliffs and near-by farm house. This is the major weakness of the book, which seems far more concerned with 'plot' than a sense of place. The day-to-day happenings, however, are very realistically portrayed, and more than make up for the slightly disappointing setting.

Once again, the descriptions of nature are second to none, although only very brief. For example, on the first day by the sea, when Daddy opens the caravan door at six o'clock in the morning; 'What a perfect morning! The sun was up, but still rather low, and the shadows of the trees were very long. Dew lay heavily on the grass.' Benjy's weaknesses (as Enid sees them) continue to be pointed out, but now are joined by the occasional 'good point' also. For example, he has 'a poor appetite', something that Enid obviously frowned upon amongst her child characters, but he admits to liking the caravan horses and to wishing they were his. He cannot swim, and hates the 'horrible cold water' of the sea but on the other hand agrees with the children that the cove 'looks lovely.' These small redeeming features of Ben's character hint to the reader that eventually, he will learn his lesson and become braver and stronger by doing so.

Indeed, Ben's presence in the story seems to be two-fold in that he is also there to teach the three main characters a lesson in compassion. Mother constantly reminds Mike, Belinda and Ann that Benjy's own mother is 'terribly ill' (the reason he is stopping with them in the first place) and that they should 'Let him get used to things.' The story is given more depth from the fact that the main characters are also forced to look at their own behaviour towards Benjy and to try to understand why he behaves as he does; because he is lonely and sad and worried. This is a world away from the child characters in the Adventure series who, when faced with Gussy or Lucian see them as simply figures of fun, and are never even reminded that it might be good manners to be kind to them. Because of this, the children in the 'Caravan' series seem to be about the most sympathetic of any of the child characters Enid created.

Once again, Enid continues the development of her main child characters by reminding us of their knowledge of the countryside, and more importantly, that they can all swim (something Ann had refused to do at first in The Saucy Jane Family, but now can apparently do under water with her eyes open!) and by Daddy suggesting he teaches Benjy to swim too. This episode is realistically treated, and the descriptions of how Daddy carries out Benjy's first swimming lesson come across very strongly indeed. Though Benjy is afraid, he goes into the deeper water with daddy and manages a few strokes whilst daddy supports his tummy. Enid herself was a very strong swimmer, of course, and her disdain for people who can't swim often comes across strongly in her books, particularly in the St Clare's and Malory Towers series'. Soon, Benjy is left shivering on the sand as he watches the caravan family all swimming strongly together out in the deeper water. It is not until a few days later, when Benjy buys a beach ball that blows out to sea, that he finally learns to swim properly. As in quite a few of Enid's short stories, particularly 'The Boy who wouldn't bathe' in which the central character is seen as foolish or cowardly, this happens quite by accident, and Ben finds himself up to his neck in water, and striking out after the ball before he even really knows what he is doing.

This occurrence makes the children gain a new respect for Benjy, as well as giving Ben some much-needed self-pride. However, it is short lived, for Ben quickly realises that no-one knew he was only struggling to retrieve his blown away ball, and realises too that he must own up decently, as the other three would do, to not being as brave as they imagined him. Happily, this gains him an even greater respect from both the children and Daddy and Mummy too. Ben is beginning to learn how to be a 'better' person — but his hardest trial is still to come.

One of the main reasons that Benjy is weak, according to the Blyton philosophy, is that Benjy has no real religion. He describes God as never feeling very near to him, and explains how he finds it hard to ask Him for things like the other children do. It seems maybe that here we can find some of Enid's own characteristics manifesting themselves within the character of Ben. Enid said in a letter to Dorothy Richards in the early thirties; 'I find it difficult to believe in [a God] that you can talk to.' (Page 109 of Enid Blyton — The Biography by Barbara Stoney) Like Enid often felt, Ben states; 'I can't really feel that He's listening.' Enid also describes Ben as being 'always afraid something awful is going to happen' and goes on, perhaps unwittingly, to put forward her own reaction to such situations; 'well, don't let's talk about it.'

Ann reassures Benjy that God will listen, and will realise how important it is if they both pray together. This is a very serious section of the book, and also one of the strongest, maybe because it was written from the heart. In outcome, it also mirrors the plot of Enid's short story of 1947, 'the Cheat' (Enid Blyton's Treasury), in which the girl prays to be helped from her cheating and is saved by the following morning. However, although, in similar fashion, Benjy's mother recovers from her illness just in the nick of time, it is ultimately less satisfying than the resolution of the short story. The reader secretly knows that, this being a Blyton book, Benjy's mother will recover eventually, whereas we have no inkling as to whether 'the Cheat' will be saved or not until the very last page. That said, the prayer being answered plot works very well within the context of the book, and is its most effective moment.

The Seaside Family also contains the most effective (and amazing) turn around of a character's behaviour in any Blyton book, for by the end of the twelve chapters Ben is answering 'yes' to all of the chores he hated to do at the books start, is making his own bed, bringing in firewood, loves living in a caravan and even offers to polish the floor! His appetite has become what Enid considered 'normal' for a boy of his age — although eating two eggs and sometimes three each breakfast time would now be considered extraordinarily un-healthy! — and he has made in Belinda, Mike and particularly Ann the kind of friends that last a lifetime. So the holiday comes to an end — with these surprising children actually looking forward to going back to school!! — and another highly entertaining addition to the 'family' series comes to a close. These illustrations are hidden by default to ensure faster browsing. Loading the illustrations is recommended for high-speed internet users only.