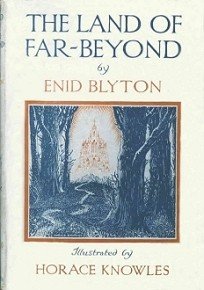

The Land of Far-Beyond

Book Details...

First edition: 1942

Publisher: Methuen

Illustrator: Horace J. Knowles

Category: One-off Novels

Genre: Fantasy

Type: Novels/Novelettes

Publisher: Methuen

Illustrator: Horace J. Knowles

Category: One-off Novels

Genre: Fantasy

Type: Novels/Novelettes

On This Page...

Reprints

1. 1957 Methuen, illustrations and cover by Horace J. Knowles

2. 1970 Dragon, illustrations Horace J. Knowles, cover uncredited

3. 1973 Methuen, illustrations and cover by Pauline Baynes

4. 1986 Methuen, illustrations and cover by Pauline Baynes

5. 1992 Dean, illustrations and cover by Pauline Baynes

6. 1998 Element, illustrations and cover by Mary Kuper

2. 1970 Dragon, illustrations Horace J. Knowles, cover uncredited

3. 1973 Methuen, illustrations and cover by Pauline Baynes

4. 1986 Methuen, illustrations and cover by Pauline Baynes

5. 1992 Dean, illustrations and cover by Pauline Baynes

6. 1998 Element, illustrations and cover by Mary Kuper

Title page from the 1973 edition, illustrated by Pauline Baynes

The Land of Far-Beyond is loosely modelled on John Bunyan's The Pilgrim's Progress (1678). Both are allegories, or narratives with a moral meaning. They revolve around a journey that is spiritual as well as physical — a journey from sin to salvation.

Allegories do not usually allow for complexity of characterisation, as characters represent abstract qualities which are often indicated by their names. To give just a few examples, two of Blyton's characters are called Kindly and Daring, while Bunyan has Faithful and Ignorance. These are types, yet both Blyton and Bunyan endow their main characters with individual traits that bring them to life. Even those individuals who only appear briefly in The Land of Far-Beyond are given finishing touches which make them memorable. One of my favourites is Bold, a cheerful, confident delivery boy who whistles merrily as he goes about his work. He shows the children that there is nothing to fear from Dame Friendly's dogs.

In Bunyan's The Pilgrim's Progress Christian travels from the City of Destruction to the Celestial City, carrying with him for part of the way the burden of his sins. He meets various characters, some of whom accompany him for a while. Despite his determination to follow the narrow path he encounters many obstacles and is sometimes led astray, though he finally reaches the Celestial City.

The Land of Far-Beyond has a similar framework. A boy named Peter and his two sisters, Anna and Patience, travel from the City of Turmoil to the City of Happiness in the Land of Far-Beyond, carrying the heavy burdens of their bad deeds on their backs. With them are two other children, Lily and John, and five adults — Mr Scornful, Mr Fearful, Dick Cowardly, Gracie Grumble and Sarah Simple. They have been warned to keep to the narrow path but they are beset by troubles and temptations on the way, causing them to stray from the path and into danger. Although Peter and his sisters finally make it to the City of Happiness, their companions do not.

The Pilgrim's Progress begins with a long introductory poem in which Bunyan explains how he felt compelled to write the book, while The Land of Far-Beyond begins with a short introductory letter in which Blyton states that her novel was inspired by The Pilgrim's Progress. As Blyton's book was written with children in mind the language and ideas it contains are simpler, though Bunyan's language too is colloquial and his sentences are fairly simply phrased for the 1600s. The opening sentence of The Land of Far-Beyond is written in the style of a fairy tale or legend: "Once upon a time, in the great City of Turmoil, there lived three children," yet in the next paragraph the setting seems modern: "The City of Turmoil was a great, noisy, dirty place, full of streets, houses, shops and market-places." This interweaving of traditional and modern elements continues throughout the book, giving it an epic quality and a down-to-earth feel at the same time, while Horace Knowles' beautiful, intricate illustrations capture the spirituality of the story perfectly.

The Pilgrim's Progress is concerned with Christian theology and characters debate issues such as the necessity of both good works and profession of faith in order to please God. Bunyan refers constantly to passages from the Bible, such as when Christian declares that he is seeking "an inheritance incorruptible, undefiled and that fadeth not away, and is laid up in heaven, and safe there." (See 1 Peter 1: 4, also Matthew 6: 19-21 and Luke 12: 33-34). Blyton's book contains Biblical references too, though they are not as frequent. Before they are permitted to enter the Land of Far-Beyond, Peter and the others have to decide which is the greatest of Faith, Hope and Love, reminding us of Paul's words in 1 Corinthians 13: 13. Yet Blyton's book, unlike Bunyan's, is really concerned with general truths and morals, rather than specifically Christian ones. Peter and his sisters meet a Guide, who informs them that "It is always hard to win anything that is really worth while." He also says: "...do not be afraid of any dangers or difficulties you come to. Face them and they will grow small — run away and they will come after you!" These were philosophies in which Blyton firmly believed and they recur throughout her novels and short stories.

As I have already stated, names are significant in an allegory and the names of the three main characters — Peter (rock), Anna (merciful; pitiful) and Patience — reveal their positive qualities. Blyton uses allegory in an imaginative way. The landscape of her book, like Bunyan's, is one of mountains, marshes, rivers, caves and castles, peopled not only with human beings but with giants and other terrifying creatures. At one point the travellers find themselves in the castle of Giant Cruelty. Peter looks at Giant Cruelty with loathing and is horrified when the giant says: "...I have often been beside you in the City of Turmoil, and you did not know it! I laughed when you threw stones at animals and birds. I made merry when you struck someone smaller than yourself! I nearly cracked my sides when you stamped on frogs! And how I roared when you called unkind names after that poor blind woman who lived in the street next to you."

The phrasing of the above quotation has an almost Biblical ring to it, yet the subject-matter deals with things that happen in day to day life. Some child readers may identify with one or two of the cruel acts mentioned and be made to feel uncomfortable about their own behaviour.

Giant Cruelty's prisoners include Misery, Poverty and Pain, and it amuses him to keep them captive and make them dance for him. As her name means "merciful," or "pitiful," Anna feels an affinity with two kind women, Mercy and Pity, who secretly bring aid to the giant's prisoners. The two women help Anna and the others escape from the castle at night, showing them that the only way out is "through the Tunnel of Disgust, up the Steps of Tears, and out through the Gate of Kindness." Pursued by Fright, the giant's "small, miserable-looking page-boy," the travellers are unable to sleep peacefully even after escaping from the castle. They cannot rest until they tie Fright up. When daybreak comes, we are told that Fright "melted away like sugar — and disappeared!" What a wonderful picture of how troubles that have plagued us all night can fade away in the light of the morning! Peter and the others learn from this experience, as they do from so many of the things that happen to them on their journey, becoming stronger and better people.

All the above inventions and ingenious personifications are Blyton's own, though some are loosely based on incidents in The Pilgrim's Progress. Other places and events are more closely related to Bunyan's novel. For example, some of Blyton's travellers visit the City of Folly which, like Vanity Fair in The Pilgrim's Progress, represents the materialism, vulgarity and false, foolish distractions of the earthly world. These things may appear attractive on the surface but they lead ultimately to disease (of both body and mind) and degradation.

Mr Scornful, the main adult traveller in The Land of Far-Beyond, is a complex and interesting character. He is a man who was wealthy and powerful in the City of Turmoil, and whose pride leads him to make many mistakes. From the beginning he treats others with contempt, saying of Dick Cowardly: "I know old Dick — he can't face hardships and always tries to go round them instead of facing up to them!" and of Sarah Simple: "She always believed everything she was told, poor creature. Never used her brain!" Yet he becomes something of a leader to the children, who feel reassured by his confident manner, and he has redeeming qualities which make him quite a sympathetic character. Early on in the book, when the children have to leave Kindly's house without Mr Scornful, Peter remarks: "I hope Mr Scornful won't be long. He's a funny sort of fellow, always turning up his nose at everything, and thinking we're all stupid — but still, he's a sort of leader, and we shall miss him." When he rejoins the children later, we are told: "The children were really pleased to see Mr Scornful again. He was a sneering, selfish kind of man, but, at any rate, he did know his own mind, and wasn't afraid of anything." The Guide warns him near the start of the journey: "You must not scorn others for stupidity or kindliness — if you do, you will lose your way and never reach the City of Happiness." As the story unfolds, Mr Scornful grows in patience and understanding but he is still arrogant and does not truly come to love others or to value being loved. He is refused entry to the Land of Far-Beyond at the end of the book because he is "a hard, unkindly man" who still has much to learn. The children are upset, but are relieved when they find out that Mr Scornful may yet be able to learn what he needs to know by travelling to another gateway which also leads to the Land of Far-Beyond. It is to Mr Scornful's credit that he swallows his pride and agrees to undertake this journey.

Compare the above description of Mr Scornful with Enid Blyton's description of herself in 1935 in a letter to her friend, Dorothy Richards:

Deep down in me I have an arrogant spirit that makes me a bit scornful of other people, if I think they are stupid or led by the nose, or at the mercy of their upbringing and environment — unable to think for themselves. I keep it under because I want to be charitable, but I have at times been horrid and contemptuous — really I have.(Taken from Enid Blyton — The Biography by Barbara Stoney, 1974)

I thought of this letter when reading about Mr Scornful. Perhaps one reason that he comes across so sympathetically is that Enid understood him, since she had to conquer her own feelings of scorn in her personal journey through life. I'm not suggesting that she based Mr Scornful entirely on herself, but that certain aspects of his character might have been drawn from her own experience.

Those readers of the Enid Blyton Society Journal who know that I am a Muslim may wonder why I admire a Christian allegory like The Land of Far-Beyond. Well, it's not really so strange. The idea of a narrow path leading to Heaven, and of travellers along the path being beset by temptations which may lead them astray, is a central theme in Islam as well as in Christianity. Muslims recite the first chapter of the Qur'an, which contains the following sentence, in their daily prayers: "Guide us along the straight path, the path of those whom you have favoured, not of those who earn your anger nor of those who go astray." Only the final chapter of Blyton's book is firmly Christian, with Christ alone having the ability to remove the children's burdens because of his sacrifice on the cross. In Islam, Jesus is regarded as a prophet or messenger of God but not as God incarnate or as one person of a "God in three persons." To Muslims, he is only a saviour of mankind in as much as those who listen to the message brought by him (and by other prophets too) will be saved. It is this, not his death upon a cross, that makes him a saviour.

The Land of Far-Beyond would make a great text for schoolchildren to study, perhaps in the top years of junior school. Discussing the messages it contains could lead to a study of how universal truths are expressed in different religions. Passages from The Pilgrim's Progress might be studied in conjunction with it too. As Blyton recommends in her introductory letter, parts of The Land of Far-Beyond could be acted out. Other follow-on activities could include cutting pictures from magazines and newspapers to create collages of the City of Turmoil and the City of Folly, or writing "what happened next" to characters like Mr Scornful, Lily or John, who have not yet reached the City of Happiness by the end of the book.

Bunyan was a Non-Conformist Christian who was imprisoned for his preaching. Blyton's works have sparked controversy over the years as well. Among other things she has been accused of producing unimaginative writing of a poor quality — but those who make such allegations cannot have read The Land of Far-Beyond. It is a timeless tale packed with striking images and ideas, as fresh today as when it was first published in 1942. Just pick up any newspaper in the twenty-first century to read reports of Cities of Turmoil or Folly — places in which parents and teachers no longer command respect, citizens are terrorised by gangs of unruly children, those in positions of authority cheat and lie, people are greedy and grasping, image is more important than substance and religion is deemed irrelevant. The Land of Far-Beyond is an inspiring book which, like Bunyan's The Pilgrim's Progress, transports us away from the City of Turmoil (or The City of Destruction) to give us a glimpse of something finer — to use Bunyan's words from his introductory poem, "a truth within a fable." These illustrations are hidden by default to ensure faster browsing. Loading the illustrations is recommended for high-speed internet users only.