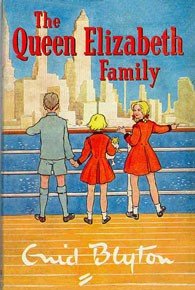

The Queen Elizabeth Family

Book Details...

First edition: 1951

Publisher: Lutterworth Press

Illustrator: Ruth Gervis

Category: Caravan Family

Genre: Family

Type: Novels/Novelettes

Publisher: Lutterworth Press

Illustrator: Ruth Gervis

Category: Caravan Family

Genre: Family

Type: Novels/Novelettes

On This Page...

Reprints

1. 1965 Lutterworth Press, illustrations and cover by Ruth Gervis

2. 1985 Sparrow, illustrations and cover by David Dowland

3. 1989 Beaver, illustrations by David Dowland, cover uncredited

4. 1997 Mammoth, illustrations by Ruth Gervis, cover by Richard Jones

5. 2017 Egmont, illustrations and cover by Aleksei Bitskoff

2. 1985 Sparrow, illustrations and cover by David Dowland

3. 1989 Beaver, illustrations by David Dowland, cover uncredited

4. 1997 Mammoth, illustrations by Ruth Gervis, cover by Richard Jones

5. 2017 Egmont, illustrations and cover by Aleksei Bitskoff

Wraparound dustwrapper from the 1st edition, April 1951 @ 4/6, illustrated by Ruth Gervis

Frontis from the 1st edition, illustrated by Ruth Gervis

New dustwrapper for the 5th edition, 1965, illustrated by Ruth Gervis

Frontis from the 1965 edition, illustrated by Ruth Gervis

This makes perfect sense, as it is made quite clear in The Queen Elizabeth Family that Mummy and Daddy have been to America before, which they did, whilst the children were staying at their Uncle Ned's farm. Mummy is able to describe the journey to America, the food, and the way of life to the children, which works for the reader because we know they had indeed been there in the previous book. Make The Buttercup Farm Family book number six, and this feeling of continuity would be lost (like it is in the modern omnibus edition, published by Dean, in which 'Farm' is placed at 'Book Six'). The Queen Elizabeth Family also seems a fittingly 'epic' tale on which to leave the series, rounding off the overall look of the six books better than 'Farm' could ever hope to do.

This time the story begins with talk about America, and how the children would love to go there to visit, much as the children reading this story in the early 1950's would probably have dreamed about going. There is also talk about the two ships that take people from Britain to America, the Queen Elizabeth and the Queen Mary 'the finest ships in the world' according to Belinda. Having thus whetted the readers' appetites, Enid goes on blatantly with the wish-fulfilment tradition of the series by having Daddy come home early from work and suggest a visit to the Queen Elizabeth and tea on board the following day. This is almost too much of a coincidence for even Enid to get away with, but after all, the book is called The Queen Elizabeth Family, so we should by now be well prepared for just about anything to happen!

After this fairytale-like beginning, the book continues in a much more realistic and down-to-earth manner, with the family going in Grannies car to Southampton, picnicking on the way, and discussing the difference between our English fields and the much bigger ones to be found in America. The family eventually arrive in Southampton and see the funnels of the Queen Elizabeth stretching up above the cranes and houses that surround the docks. Enid describes the sights and sounds of the Southampton docks with relish, calling it a 'wonderful place' and describing the big and small boats and the 'fussy little tugs', the 'hootings and sirens and hammerings and shouts!' The children are more than suitably impressed by their first proper glimpse of the ship they have come to see, being amazed at its size as it towers above them, and Enid can't resist a little patriotism slipping in when she has Daddy saying ' She's grand...I'm glad she's British. No one can beat us at shipbuilding. We've been ship-builders for centuries — and here's our grandest ship so far!'

The following chapter gives us a glimpse at the inside of the Queen Elizabeth; a tour of its decks, function rooms, cabins etc. It ends with the children wishing they could stay on board and travel to America, and of course, it isn't too long (chapter five, in fact) that the wish-fulfilment is at work again and the children are seeing their dreams come true, sailing across the Atlantic for two weeks in New York. It is at this point that the story really takes off, as it did in The Pole Star Family as soon as they set sail. Once again this is because the voyage on the Queen Elizabeth is a factual one, mirroring the time Enid spent on board the great ship when she too sailed to America in 1948. From chapter five Enid fills the book with interesting details about life on the Queen Elizabeth, from the size of the beds to the cork life belts, which Belinda feels very privileged to call her own.

Enid charts the course of the voyage, from the tugs pulling the great ship backwards out of the harbour, to its journey along the coast, across to France and then finally across the 'enormous Atlantic Ocean, hundreds of miles from anywhere.' The reader gets a great insight from this description of just how Enid must have felt when she began the same voyage. With her descriptions of the 'vast' ocean, and the thought of the ship ploughing on through 'the dark waters' Enid manages to give us a sense of the insignificance of even that great ship when compared to the vast power of nature itself. As usual, there are descriptions of food to help wipe these lost and lonely feelings away. At breakfast the following morning the children are faced with 'porridge, cereals, iced melon, stewed fruit, bacon, eggs, steak, fish, omelettes, chops, ham, tongue...' and are told by the stewardess that they can eat as much or as little as they like. Once again, as in most Blyton books, the children take this in their stride, the meals becoming the most important part of the voyage. As Mike says; 'If all the meals are like this, I am going to enjoy this trip!'

Enid goes on to describe in great detail the size and splendour of the ship, giving us a real sense of actually being there with the children. We hear about the 'miles and miles' of deck, the big swimming pool, and the beautiful library (where no doubt Enid spent a little of her time?) with 'hundreds and hundreds of books waiting to be read.' Enid describes the shops, the sports deck, and the games to be played, such as 'shuffleboard'. There are wonderful descriptions of the sea, spread out all around them, the spray on their lips, the wind and the sound of the waves against the ships sides, all combining to give us a real sense of place. Enid tells us of the little cups of hot soup brought around by the stewards in the middle of the morning, the gym, complete with 'bucking horse', the lunch menu's which are like books they are so thick, the church services and lifeboat drills. Once again, it is easy to tell that Enid is writing about the things she actually experienced, and once again this gives the final instalment in the family series its real thrust and power. The descriptions of the ship 'rolling' in the gale, how it feels worse when the lights are off; 'down — down — down — to one side, until the children really thought it must be touching the water — then up, up, up, and over to the other side — down — down — down again, lower and lower' are second to none, and really begin to make the reader realise what it feels like to be sea sick! Ann's fear that it might roll 'so far over that it didn't come back,' must have been one of Enid's fears during her journey to America, so succinctly is it voiced.

Enid's one moment of getting muddled seems to be with the talk of clocks, and the time being set back and forward as they cross the Atlantic. Blyton describes how the clocks are put BACK an hour every day, and tells us that this means they LOST an hour a day. On the return journey the clocks will be put ON an hour, making each day an hour longer. Surely the opposite would be true, with clocks going back an hour GAINING an extra hour and clocks being put forward LOSING an hour...

This aside, The Queen Elizabeth Family is an excellent book: a journey to America and back that is filled with fascinating facts set down in a highly entertaining way. The descriptions of New York life are very telling when one considers that Enid never again ventured to America herself, and found the pace of life too fast for comfort. She describes how people talk 'like Mickey Mouse talks in the films' and the way in which the taxis drive 'very fast indeed'. She talks of the noise and bustle of the city. Mike even states, much as Enid probably thought, 'everything goes fast in America — the taxis, the lifts, the parties — and even the time!' She gazes with the reader in wonder at the gigantic meals, the strange-sounding food, such as 'waffles', 'hamburgers' and 'hot-dogs' — all familiar to us as a nation in 2005, but obviously very new to the likes of Enid, who tended to be suspicious of anything that wasn't British. She takes us to the top of the Empire State, where Ann, usually the most spiritual of the three children, notes that they must be 'very near to Heaven' up there. She describes the feeling of being 'on top of the world', and treats us to the sight of an aeroplane flying along below us.

Enid crams the trip to New York into only two chapters, and in doing so helps to create that feeling of 'a city that never sleeps', always rushing and hurrying and never enough time to do anything. This is a very effective technique, giving the reader the same sense of breathlessness that the children feel, as we have two weeks in New York crammed into two short chapters. Soon it is time to go home, with the children wondering if an hour in America is really only half an hour, they go by so quickly!

The family spend much of the last chapter reminiscing about 'dear old England' — 'the little island far away across the ocean,' probably very much as Enid did as her time to leave America drew nearer. They talk of 'its primroses and springtime', 'watching the first green blades come through in the fields of corn' and of 'treading on the first patches of ice when we go to school in the winter.' This chapter sees Enid at her descriptive and poetical best, and it is interesting to note that, once again, she is describing England, one of the few places she ever allows herself to become sentimental over. Daddy sums up this very strong feeling of Enid's when he says, near the end of the book, 'It's good to travel...We see how other people live and make themselves happy — and we love our own home and country all the more for seeing other people's. Each of us loves his own country best, and his own home best and his own family best.'

This love of her own country and her own people made Enid the writer that we know and love today. Some people may choose to criticise this outlook in a world where we are now all supposed to be one community, but we must remember that this was a woman born in the Victorian era speaking in the early 1950's, and we should respect her beliefs. After all, I don't believe they are very far removed from the feelings many of us experience today when returning to our own countries after a long journey or holiday, wherever we choose to live. As Enid goes on to say, that island far away was 'their home — the home they loved and wanted...Home to England, dear old England.' These illustrations are hidden by default to ensure faster browsing. Loading the illustrations is recommended for high-speed internet users only.