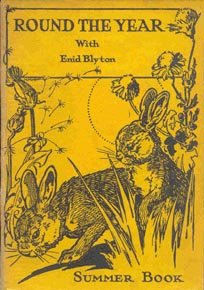

Round the Year with Enid Blyton - Summer Book

Book Details...

First edition: 1934

Publisher: Evans Brothers

Illustrator: Enid Blyton and Kathleen Nixon

Category: Round the Year with Enid Blyton

Genre: Nature

Type: Courses and Encyclopaedias

Publisher: Evans Brothers

Illustrator: Enid Blyton and Kathleen Nixon

Category: Round the Year with Enid Blyton

Genre: Nature

Type: Courses and Encyclopaedias

On This Page...

Reprints

'Tale of the Tadpole' (is it an intentional pun?) presents a frog's life story together with an accompanying diagram illustrating the process. Tadpoles originate in slippery spawn and grow larger until a frog or toad appears in the pond or perhaps in a nature lover's terrarium. It makes interesting reading and many hints are supplied to assist with the process of keeping them as pets. You mustn't use tap water in the aquarium, so always bring some pond water back to use for your creatures and in the home environment a small piece of meat can be tied to some string and hung in the water for your tadpoles to nibble - but it mustn't be left in for very long otherwise the water could be affected. Tadpoles develop into tiny frogs that can sit very comfortably on a sixpenny bit and we're advised to place them back in their pond when they reach this stage because they feast on flies and other insects, which one might find a little difficult to supply.The second chapter tells us all about the growth of flowers which will a subject of interest to many readers. Sepals and petals, pistils and pollen are mentioned of course and there's a diagram showing the various parts. Pollination is explained and it's enlightening to learn how different plants have adapted their pollinating techniques to accommodate the various insects that descend on them.

The most important entity that ensures our life and well-being must be the sun, and Enid Blyton hasn't quailed in taking on such a gigantic subject. Her account deals with size, distance from our planet, and how the great star's powerful heat can affect us. We set our clocks by the sun and whilst enjoying the light it brings, millions of other people reside in darkness on the other side of the world. The sun warms the ground we live on so it acts as a sort of radiator, and the clouds are a kind of blanket because they tend to keep warmth in. The chapter's end lists many things done for us by the sun, and these include the simple action of drying our clothes on a clothesline.

The swift is classed as one of the fastest birds on Earth, and Chapter #4 tells us all about this particular bird together with another associated avian species - the swallow. These are well known to Britishers and we're told there are actually three different kinds of swallows - barn swallows, house martins, and sand martins. Apparently the swift doesn't belong to the same family, which is a surprise because they're often associated and look vaguely the same, but who are we to question the experts? In the accompanying picture we can see a slight difference in the barn swallow with its longer tail. The swift is described as sooty-black all over so that's one way of distinguishing it and the feet of all four birds are 'weakly.' Seeing they shoot around in the sky catching food on the wing, they appear not to have all that much use for their feet - in fact, the swift's are described as 'almost useless.' These birds leave our shores round autumn and fly off to warmer lands, yet in April their built-in homing systems allow them to return quite unerringly to the very villages in which they were born, so it looks as if the scientists of the world have their work mapped out for them. Mind you, theories abound and these involve magnetic fields and internal compasses so we're well on their way to solving the conundrum. Enid Blyton's account makes this a very interesting chapter.

Next we enter the caterpillar world and who's never cared for a few of these grubs in times past? The transformation into butterflies is quite miraculous and Enid Blyton has supplied instructions for creating elaborate containers such as an earth-filled flowerpot and glass cylinder, while the second example employs a small box mounted on a jar. Another diagram illustrating something looking like a homemade rocket has words such as 'sleeve', 'lamp chimney,' and 'muslin' accompanying it. The muslin is shaped into a tube that allows part of a growing plant to be enclosed inside. The illustration next to it shows us how to use a 'lamp globe,' cotton wool, and more muslin for an alternate enclosure. Page #48 demonstrates two more ways of creating comfortable quarters for our pampered pets - whereas my own housing requirements for caterpillars consisted simply of a container such as an old bucket, filled with earth and plants. The avid Enid Blyton followers are definitely working to more specialised instructions and, presumably, they can understand how to create a 'muslin tube.' Information dealing with the caterpillar life cycle abounds of course; there are also plenty of hints as to feeding and our author instructs us to clean the cages regularly.

'Flowers For You To Find' is next and there are plenty of them blooming seeing this booklet is labelled 'Summer.' It might need a little searching though because Enid Blyton has included such flora as 'Blue Bugle, 'Birdsfoot Trefoil.' and 'Field Convolvulus.' There are almost forty named flowers so after reading the descriptions a hunting we will go with high hopes that at least a few will lend themselves to being tracked down. To help with identifying the quarry, several are pictured and amongst them I can recognise a few names such as 'Groundsel' 'Pimpernel' and possibly 'Jack By The Hedge.' Many readers have surely heard of more and will even be able to identify them. There's one called 'Dead-Nettle.' Now, I wonder why it's so called - surely it's not actually 'dead.' The name 'Hemlock' would be familiar of course and 'Shepherd's Purse' has been mentioned several times in the EB collection of books.

'Story of the Bee.' That's what page #61 brings and this subject had to be included of course considering the part that bees play in flower reproduction. Enid Blyton quite rightly tells us she could fill the whole book with facts about these insects because it's such a wonderful tale. First of all we re-learn several things such as the pollen pockets on a bee's hind legs and how they fertilize flowers which is apparently not the case with our authors own greenhouse at 'Old Thatch.' She has to brush pollen from one flower to another if she wants them to grow ripe red fruit. Other information dispensed concerns beebread, Royal Jelly, and facts concerning hives. There's a photograph showing five children watching a beekeeper who's holding a rack covered with bees and, rather oddly, no one's wearing any protective clothing. Possibly the insects have been subdued with smoke or something. The inner hive is dealt upon and we're informed as to how bees can actually reduce the temperature inside by fanning their wings to cool the place down. No, I'm not making that up. There are three kinds of bees - 'workers,' 'drones, and of course the 'queen.' Drones are just that - they don't work and therefore possess no pollen pouches as do the other inhabitants. The queen lives very royally with attendants and a bodyguard at hand and when she moves about, the others make way for her. If the hive becomes too full she takes some of the bees away to start another colony. One sunny day we may observe a sudden swarm pouring out of the hive and gathering perhaps on a tree whilst scouts spread out to find suitable accommodation, and an accompanying photograph shows bees by the score that have swarmed on a gate. This is where the bee-keeper comes in. Not wanting to lose any of his honey-makers, he places an empty hive nearby - thus making it easy for the bees to locate a new home. Going by our standards nature is certainly cruel because in the old hive a newly formed queen goes round stinging any potential royal grubs to death. The drones will also suffer a sad fate as well because the workers will set upon them, the drones' wings will be bitten off, and then a great casting out occurs whereby the lazy former-inhabitants will wander around and die. The chapter ends with a brief dissertation on the friendly bumble-bee (or 'humble-bee).

Another popular subject is dealt with in the following chapter - silkworms. Enid Blyton makes it all sound so easy when she tells us you can buy a hundred silkworm eggs for a mere shilling! I don't think I've ever seen silkworm eggs for sale but they're obviously around. May is the month for indulging and we're told what the eggs look like, how they hatch and there's also a photograph showing different stages in a silkworm's development. If there's a mulberry tree handy to your place then you're home and hosed because silkworms apparently love their leaves. Lettuce can also be used for food though. Even an author of renown seems to have some spare time because in Old Thatch there are cardboard-box lids inhabited by silkworms and each container needs to be cleaned out each day. Do not be alarmed if one or two of your pets look as if they're ill and won't eat - don't call the doctor because this behaviour means the silkworms in question are going to change their skin. This happens four times in a silkworm's life and maybe it's because they're so greedy. The chrysalis stage arrives after about six weeks and hints are supplied for those collections that may be in a classroom setting - you can place each silkworm in a bag and date them for the record. A cocoon is woven and if you like, the silk can be unwound for further examination. Eventually the cocoons will yield moths and what happens next could be a subject for philosophical comment because, after laying hundred of eggs, a silkworm moth simply dies!

Trees and Seaside Creatures fill the last two chapters. Several types of trees are discussed and illustrations of various leaves are supplied. Chestnut, Willow, Oak, Beech and Elm would be familiar names to most of us and the 'Things To Do' section contains such exercises as drawing leaves and searching around for them. You can also look up reference books to discover further details and of course we have access to limitless information these days. You can make a 'Tree Book' for your drawings and notes although it might be easier to use a computer for this.

As some of us may be going to the seaside for a holiday, we're told what to look for in various rock pools that are just waiting to be discovered. Enid Blyton explains to us how the shrimps have a different colour from ones bought in shops because the latter have been boiled. The prawns look as if they're wearing suits of old fashioned armour and during the moulting process it splits. The hermit crab tucks its tail into an empty shell and moves around feeling quite safe no doubt, and I wonder how many people know that a crab has ten legs. I guess they don't end with feet but speaking of tootsies, we learn that a starfish has " ... hundreds' of tube feet." Imagine if it had to wear shoes! Starfish arms or fingers, of which there are usually five, are sometimes called 'rays' and if one is severed then it's simply replaced. Another queer sea creature is the jelly-fish, and its method of obtaining food is by means of poison darts so we must be very careful not to approach any that are observed floating in the water. Diagrams of other sea creatures are displayed, and after mentioning egg cases that can be discovered on beaches, the summer booklet ends because there's no more space to elaborate on cockles, mussels, limpets, periwinkles and other fascinating creatures of the sea.

The summer section of 'Round the Year with Enid Blyton' has a frontispiece depicting how a butterfly uncoils its long tongue to suck 'honey' from a flower. Now is it 'nectar' or 'honey?' That is the question. One source names the nectar as a 'sweet liquid produced by the majority of flowers.' People who are into Blyton will recall the nectar sucking process being dealt with in other nature stories, and of course we can observe it for ourselves during the summer.

Amongst the photographs is one of a comfortable looking toad, fields and hills basking in the sunshine, a sand martin, and a silkworm moth.

#1:

A sixpence is not even 20 millimetres in diameter so a newly formed frog is small indeed.

#3:

Another excellent means of drying clothes is of course the utilisation of wind power.

#7:

Despite being pampered to the nth degree, the queen must lead an overall boring life stuck in the centre of a hive laying eggs day and night.

Back in the early days when 'Round The Year With Enid Blyton' was written, Old Thatch was Enid Blyton's Buckinghamshire home.

#8:

It's worth learning more about silkworms and the rather cruel end that often comes to them when in the pupa stage. Apparently they eat nothing once they turn into moths so their lives appear to be that of a rather futile existence. Spend a few weeks growing and changing around and then, when maturity arrives ... snuff it. If the purpose of their lives is to simply produce eggs that yield more silkworms that produce more eggs and so on, why bother creating them in the first place? At least, when we ourselves mature there are many years (if we're lucky) of travel, raising families, and exploring the environment. Lesser animals and insects can also look forward to a bit of fun, but the poor old silkworm is doomed.

A shilling back in the thirties might equate to £3 or more in today's currency.

Trivia: It appears that one cocoon can yield round a mile of silk fibre!